This week I looked at a couple of the virtual reality experiences put together by the Chicago History Museum as a part of their Chicago 00 project. In particular, I chose to try out their “1929: St. Valentine’s Day Massacre” and “1933/34: A Century of Progress” virtual reality interactive videos.

Overall, I was very impressed with the use of VR as a tool to bring history to life and to make archival photos and documents accessible to audiences who might otherwise never have sought them out. Frankly, I was shocked by how the VR complimented the narration and the photographs in a way that introduced value that would not have otherwise existed because of the use of technology.

I tend to find that more often than not this isn’t the case with the use of new technologies in museum settings. Sometimes just because a new technology is there and it is cool, it gets used – almost as a ploy – and the visitor and/or user can sense that. Without a deeper purpose or a reason that the technology is needed to tell the story, it can be more of a barrier to engagement than a facilitator of accessibility.

As someone who has truthfully never used VR before, I was impressed that the experienced was presented to me in the form of a YouTube video. No complicated apps to install, no new commands to learn, and better yet, I could participate with or without a VR headset. (I realize they are relatively accessible, but really, who has the time?) I also liked that there were three ways I could interact with the presentation – there was a video about the presentation, an interactive VR-ready YouTube video that contained the presentation and a Google Maps street view option wherein the photos were embedded on a sort of virtual walking tour. I like options and all three of these are relatively straightforward. I did find the process of getting to these options on the Chicago 00 site a little more difficult than I expected but not enough to put me off. I’m focusing my review on the VR videos because I did not find the Google Streetview very easy to navigate and it didn’t have the same effectiveness without the narrated storytelling integrated in the video version. I think for people who wanted to explore but had difficulty getting the video to load because of hardware issues, lower speed internet connections, or general anxiety about technology this Google Maps version may have been a suitable replacement, but since we are talking about VR, let’s talk about the actual VR version.

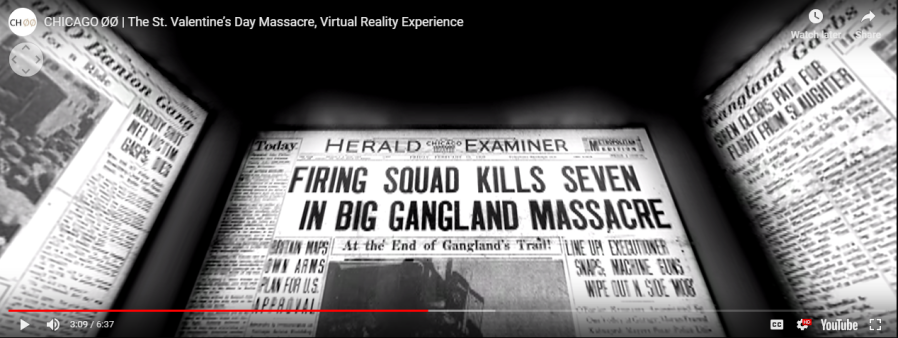

First, let’s talk about the St. Valentine’s Day Massacre project. I can’t be sure if it was because it was my first time using VR or if I just went a little spin-happy, but I did struggle to figure out which direction I was supposed to be facing when the pictures shifted throughout the presentation. I liked that I could “wander” around in circles, in some ways it made it feel more like a real tour, but I wonder if the video refocused me occasionally if this would have made it a bit easier to navigate. I was surprised and delighted when the street view disappeared, replaced by the front pages of four newspapers and later other archival documents. Those are dimensions that would be lost on a walking tour, which is why VR provides a unique opportunity to create an experience that is rich in its own right without just mimicking something else but with more technology. I also found the narrator’s statement that this project was an attempt to anchor the events of the St. Valentine’s Day Massacre to this particular geographical place in lieu of a plaque fascinating. I wonder how an amateur audience would feel about this statement. I know nothing about the history of the neighborhood or prior attempts to memorialize this event, but I assume based on the sub-text of that statement that there is one and that it is surrounded by conflict.

The second video I watched seemed to lend itself to VR a little more easily, both in format and in context. Format because the impermanence of the structures and event resulted in massive documentation to attempt to preserve it, thus recreating it through a technological model seems “right” somehow. But also, because, as they explained within the presentation itself, the theme of the fair was progress – including scientific and industrial advancements – of which VR can certainly be considered one. My favorite part about this presentation was the addition of the Goodyear Blimp floating in the sky. At first, I thought the Google Mapping car had simply photographed a low swooping airplane until I looked a little more carefully. I would have really loved to have seen different multimedia, perhaps even video clips integrated in this presentation. I think it might have made it more dynamic and interesting. I found this video easier to use than the first one, I am not sure if that is because I had another VR experience under my belt by this point or if it was because we were often looking at more distant vistas which means that it was easier to figure out where I was supposed to be looking. I do also think there were more 360 degree views in this experience than the first, since we weren’t looking at only one side of the street.

I think the main question to ask about whether it is worth creating a virtual reality experience in a museum is (aside from can you actually afford to execute it) can it do something for your audience that they wouldn’t be able to get another way. In the case of Chicago History Museum, I think the answer is yes. These VR experiences were carefully crafted to both appeal to and provide unique opportunities for members of their far-reaching audience who may not otherwise engage with these materials. I think potential users could include classrooms of students who couldn’t easily manage field trips to either the museum or historic sites referenced within the videos. I think they could also potentially appeal to people who are disabled or unable to venture downtown for other reasons like lack of transportation. One drawback to creating an outreach tool that is so completely digital and dependent on e-devices and high speed internet connections is the inequity arising out of the digital divide.

However, I do not see this as a reason to avoid these media, public libraries, schools and other facilities are bridging these gaps – and creating engaging material that people want to seek out encourages those who might ordinarily be disadvantage in these ways to seek out ways to overcome these disadvantages.

TL;DR I am deeply impressed and inspired by what Chicago History Museum has done with these videos. I can’t wait to see what other museums are able to accomplish along the same vein. I look forward to the growth of VR historical narrative emerging from museums around the world in the coming years.